The Boycott Economy

Monia had a recent post over at her Substack about the impact of Livejournal on fandom culture and social justice. Or as she put it:

One of the questions that tickled my interest was, “When did social justice get mapped onto obscure fandom for fictional characters?”

One of the comments on her post raised the issue of the on-going Hybe boycott. For those not up-to-date on K-Pop fandom, a subsection of fans is demanding Hybe disavow Hybe America CEO Scooter Braun because of his support of Israel.

"Korean and International ARMY (BTS' global fan base) demand HYBE divests from Zionism and Zionists in the industry," read the message displayed on the screen of the truck.

"If our demands are not met, ARMY will continue to push for you to meet our demands. Do not look away when the same thing that happened to your Korean ancestors is happening to Palestinians. We ask that you stand for humanity, for the right side of history and against violence."

To the outside observer, this probably seems like a fandom run wild. Who are these fans to demand such things from a corporation? Why would they even care about who sits on the Hybe America C-Suite?

Well, the answer is that Hybe itself created these fans and now are having to deal with the fallout.

Let’s rewind a bit to set the scene. There have always been a subset of musicians and songwriters who engage in political speech through their music, even in popular music. Korea is no exception. CCR’s “Fortunate Son” became an Anti-Vietnam War anthem; Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” decried racism against Black Americans. Korea had its own political songs with their own domestic-focused meanings—Shin Joong Hyun's "Beautiful Rivers and Mountains” is probably the most famous example (he was persecuted and tortured by the government for his defiance).

Those “Fathers of K-Pop” Seo Taiji and Boys were also constantly butting heads with censors for both their lyrics and stage outfits. But the focus of Seo Taiji and Boys were on issues their teenage audience would identify with: “Classroom idea,” focusing on the education system, “Come Back Home,” on being a teen runaway. The artists of what we now call First Generation K-Pop followed Seo Taiji and Boys in writing songs that spoke to teenage concerns. The first album from S.M. Entertainment’s foundational 1990s group H.O.T. was literally called We Hate All Kinds of Violence in response to contemporary Korean teen concerns with school violence.

The politics of teenage pop music are meant to be cathartic to teenagers. Pop songs may become anthems of political movements or the soundtrack to political change and upheaval but until Wyld Stallyns united us all in a global era of peace and unity, pop music may share your political opinions but consuming a pop song will not actually change the world in any meaningful way. Despite decades of singing about it, school violence is still a huge problem in Korea.

Okay, so the problem with songs about problems facing teenagers in Korea is not only that these issues may not translate to a global export audience but they’re not necessarily the face that Korea wants to show the world. And when the domestic teenage pop fully morphed into Export K-Pop somewhere in the mid-late 2000s into the early 2010s, the politics of K-Pop songs became the politics of cultural soft power and improving Korea’s image abroad.

There’s nothing inherently good or bad about cultural soft power, it is what it is. America certainly engages in it through our consumer culture. India does the same via movies. Japan has rehabbed their image in the West via anime and manga. Thailand exported their cuisine.

K-Pop companies happily accepted funding from the Korean government and built global K-Pop into its own gated community with its own internal concerns and dramas. When idols met the censor’s hammer it now tended to be for things like Block B angering K-Pop fans in the large market of Thailand or for things that might upset the large conservative fandom in places like Southeast Asia or the Middle East like Winner’s “Island” getting sniped for being too “homosexual” or BigBang getting got for party rocking too hard.

Which is not to say that Korean pop music couldn’t still discuss domestic political issues but the overlap with export K-Pop was small to non-existent. A 2014 Hollywood Reporter article lists a handful of Korean artists speaking out publicly about the Sewol Ferry disaster—none of them are export K-Pop acts. (Although there are idols mentioned putting a yellow ribbon on social media in support of the victims.)

K-Pop fans wanting their favorite artists to speak up in support of the victims were left to semiotic analysis and donations both announced at the time and quiet donations “uncovered” at a convenient time.

This is not to say that the artists don’t care or didn’t support causes privately but publicly speaking out as an idol was neither expected nor encouraged.

But as Monia points out in her post, Western/American fandom was becoming increasingly wrapped up in things like the 2009 Racebending clusterfuck. Rightly or wrongly, fans wanted to see their concerns with issues like race, gender, and sexuality, addressed by the artists and creative properties they loved and over the next decade or so, they increasingly would. Whether that was pop stars like Lady Gaga shouting out her LGBTQ+ fanbase with “Born This Way” in 2011 or Childish Gambino speaking to the Black American experience with “This is America” in 2018.

The trickle of support from George Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh to 1980s charity single “We Are the World” has become a flood, especially in the wake of the 2020 BLM movement, and fans now expect American pop stars to speak out on a range of progressive political issues—the most recent of which is the crisis in Gaza.

Circling back around to the top of the post, there’s a good reason that fans of Hybe acts expect Hybe to speak out about the crisis in Gaza.

But why is that if—as I just explained—global K-Pop (Hybe’s primary medium) is only political in terms of a soft power boost of the Korean image abroad?

Well, that is because when Hybe entered the American market, the company began using the American pop vocabulary. No, not English—social justice.

It began with a trickle of prominently placed articles calling the Grammy Awards “racist” for not fêteing BTS, not so subtly saying that the middling reception of their music by western critics was also racist.

But things picked up in the heat of the 2020 BLM movement with a massive donation from BTS to Black Lives Matter in June 2020 and articles aimed at the fandom audience via outlets like Weverse Magazine, explicitly linking Hybe acts to the struggles that Black and sexual minority musicians faced in America, despite the fact that these acts were neither [emphasis added]:

But BTS has broadened the road, and its significance runs deeper than adding an extra option - in this case, Asian - to the diversity spectrum. In a country with bias and discrimination against boy bands, minorities and alternative masculinity, BTS’ first English language single “Dynamite” being produced as disco, is very meaningful from both the history of U.S. pop music as well as the social context – especially so when the song depicts the joy of vibrant daily life in this day and age. TOMORROW X TOGETHER’s “Blue Hour” utilizes disco to represent the boy band’s fresh concept; the song sings about a special moment of happiness in a world that could be either real or imaginary.

Whether or not you agree with this reading, the fact that it’s so explicitly spelled out like this in an in-house magazine post indicates to me that the Hybe media strategy was aimed at the types of fans who were concerned about the progressive political issues in America like Black Lives Matter.

And it worked.

Unfortunately for Hybe it seems to have worked a little too well.

While musicians of all genres are speaking up for Palestine, it’s not unreasonable that fans who were so proud of Hybe’s progressive politics for donating to Black Lives Matter are frustrated with their silence on this issue. The boycott, seen through this lens, is not a narrative of Entitled Fans but one of fans sold a bill of goods (in this case, supporting a politically progressive company) that is not being fulfilled.

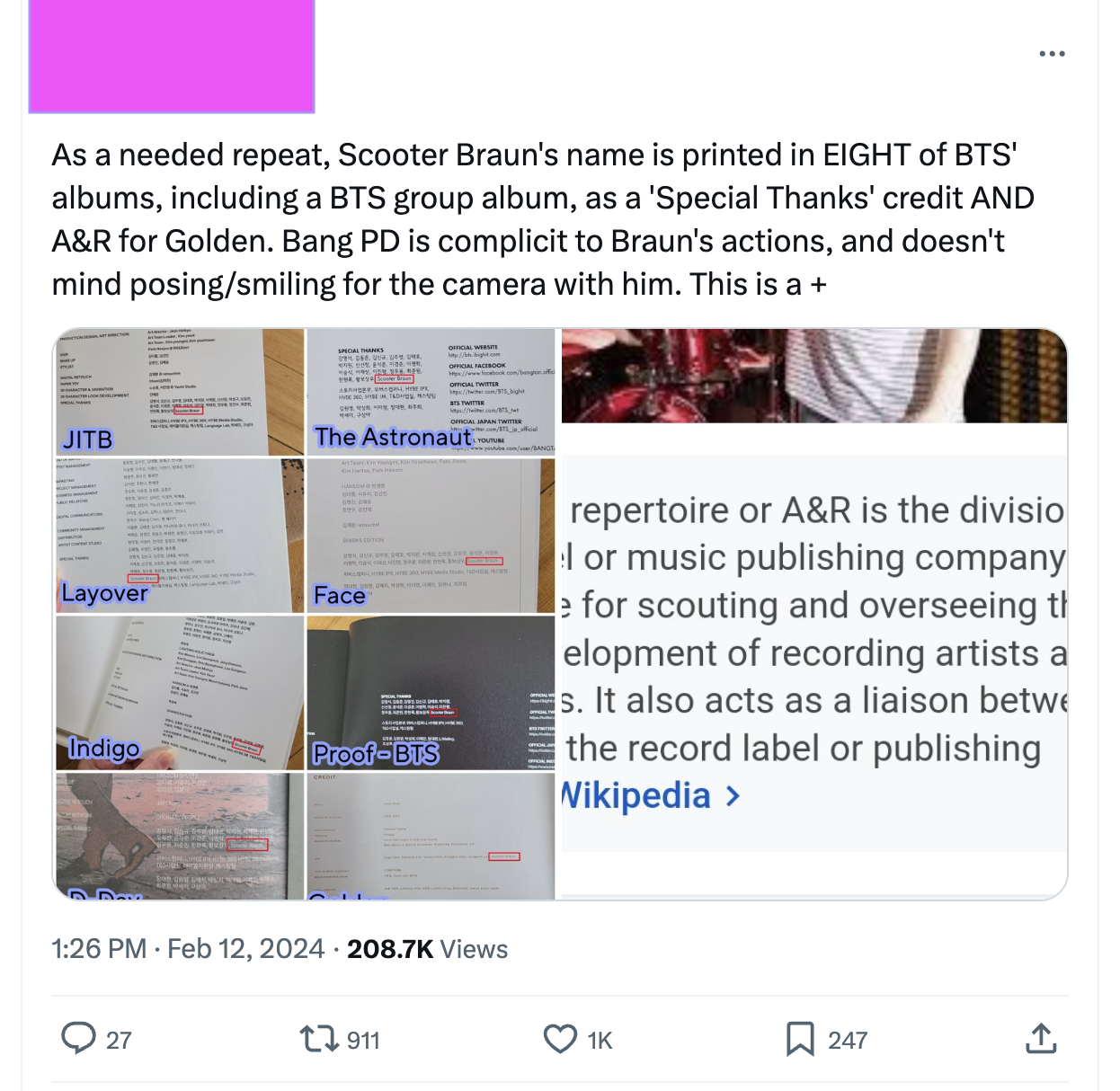

This is something that has popped up before—a concert in Saudi Arabia, the flippant use of a sample of a Jim Jones speech—and certainly fans expressed disappointment and some even left the fandom, but the Gaza issue feels like it’s hit a bigger nerve. Maybe it’s because the looming presence of Scooter Braun and his very public support of Israel is harder to handwave away. The Saudi concert could be spun as a gesture to fans in the Middle East; the Jim Jones sample explained as the choice of an unnamed producer who was unaware of the speaker’s history. But how do you spin Hybe figurehead Bang PD’s close relationship with Scooter Braun?

The end result of the boycott is not yet clear. Will it matter? Is this a turning point or merely a small roadbump? Only time will tell. As the industry continues to implode, the shedding of politically aware progressive fans may not even matter in the long run…

As an addendum to this post, not soon after hitting “Save” I spoke with a friend at a not-online American BTS fan event and asked her to ask around if anybody had heard about the Hybe Boycott. Nobody knew what she was talking about or that there was any controversy.