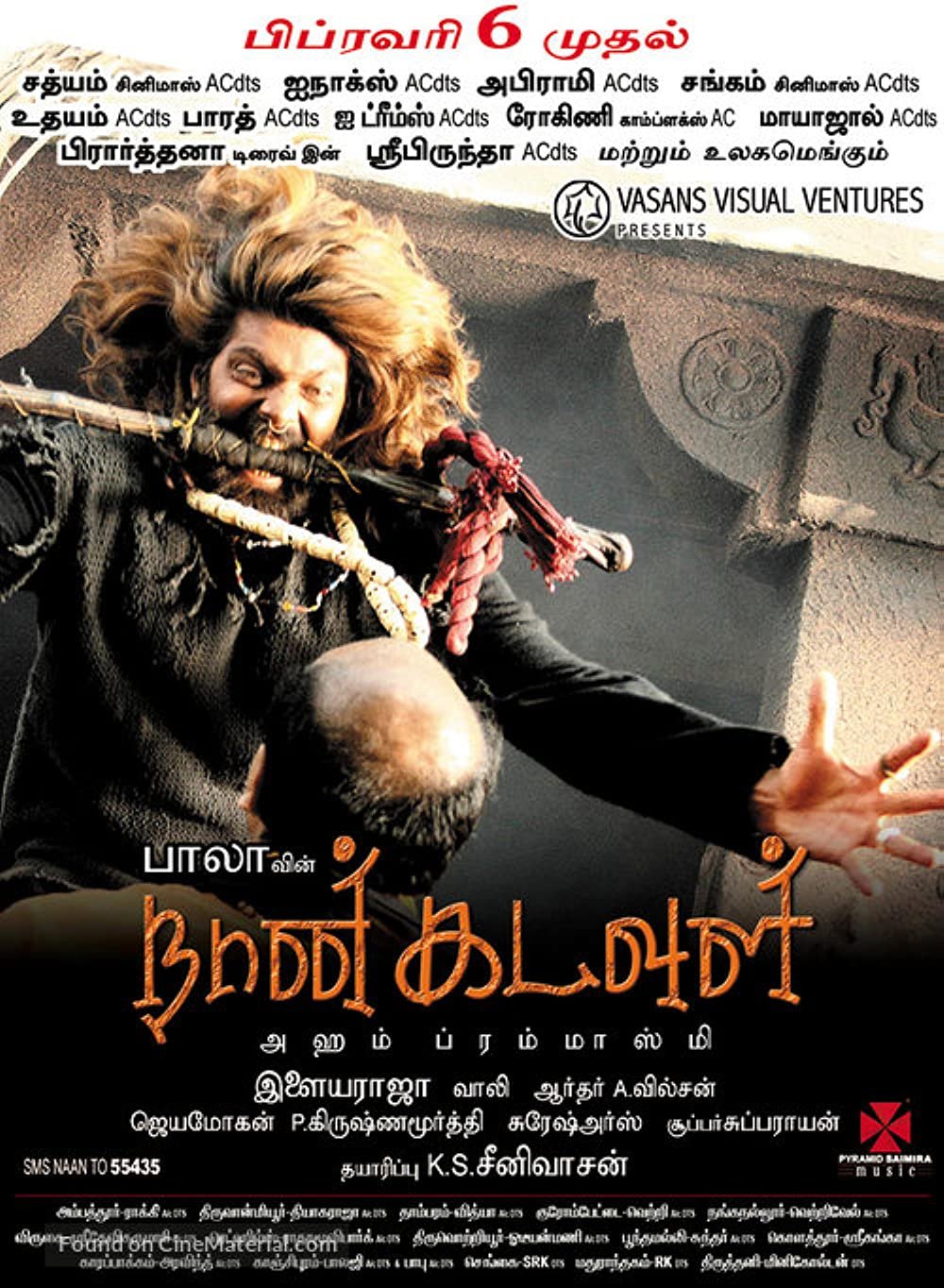

Naan Kadavul (2009)

The experience of watching Naan Kadavul is akin to that of getting a headbutt from the main character of the film, an aghori played by Arya. And I mean that, of course, in the best way possible: watching Naan Kadavul knocked everything else out of my head. Director Bala has crafted a remarkable film on the nature of God and life and on the things we do to survive. Although it’s set among a community of beggars, Naan Kadavul is no soppy tearjerker or pretentious art film, it’s got a biting wit and is packed full of gallows humor... sometimes literally.

Naan Kadavul begins with a father looking for his lost son in what looks like Varanasi, on the banks of the Ganges. The father had been told by astrologists that his son had an unlucky horoscope and in order to avoid tainting the rest of his family, he needed to cast his son from his sight for fourteen years. Now that time is ended and the father wants to take his son back home. There’s just one problem—his son (Arya) is now an aghori who has been completely taken over by the spirit of God.

In a parallel story, we meet a group of beggars who are owned by a real jerk of a boss (Rajendran). Every day he sends them out to beg and in the evening, he collects the money. One of the boss’s middle managers (Krishnamoorthy) is captivated by a blind woman with an incredible voice (Pooja) and captures her for his gang.

The stories of the blind woman and the aghori finally intersect in an orgy of violence but how and why is something I’ll you find out when you watch the film—and you should watch the film.

As demonstrated in Pithamagan, director Bala has an incredible eye for two things. The first is the role of filmi songs to bring people to together and to provide catharsis. The second is to find the human soul on the fringes of humanity. Pithamagan gave us a look into the souls of a con artist and a man raised in a graveyard—two characters living outside of mainstream society. Naan Kadavul, too, plays with both of these themes in the narrative track that follows the blind woman.

Bala’s depiction of the community of beggars is nothing short of remarkable. I wish that the credits of the film had been translated because the cast of disabled actors he assembled was simply mind-blowing and I have never seen a film that treated its disabled subjects with more respect. Bala understands our impulse as an audience to gawk and feel pity and he indulges us for maybe 3 minutes before he switches perspective. As the beggars are introduced in a song picturization, we see their hard lives begging and being beaten with that full Slumdog Millionaire-style condescension. And then Bala does something unexpected—he shows us the beggars laughing and good-naturedly dancing to amuse themselves. Suddenly, the beggars aren’t there for our pity, they are just human beings living their lives.

The community of beggars provide the raw human heart of the film on their own terms. A small man with deformed limbs has a quick wit and a (metaphorically) big mouth and enjoys cracking wise at all alike, laughing heartily at his own jokes. A woman with two deformed legs, unable to walk, plays along in fake-marrying their overseer Murugan when he is too drunk to realize what’s going on. A grandfather tenderly cares for his mentally disabled granddaughter. A hijra in a shabby black wig gamely dances to an item song for the amusement of the police. The biggest beggar, who speaks in the childlike voice of the castrati, protects money for his friends.

Pooja, Rajendran, and Krishnamoorthy have the three biggest speaking roles and all three are fantastic. Pooja’s character is completely at the mercy of her captors and yet she possesses a strong backbone and a deep sense of self-preservation. She is timid at first with her new community but once she realizes that she is safe and cared for, she easily settles into her new life and is unafraid to voice her opinions. Krishnamoorthy is playing the somewhat ‘gray’ character of Murugan the overseer and does a fine job showing the tensions at war within him. Rajendran is pure evil but we get a hint of what drives him when a bigger boss shows up and begins treating him like a small town huckster. Then we know what evil really is.

Arya’s track is almost completely separate from the beggars’ track. The aghori is God in heaven, interacting only with the humans in order to pass judgement and then carry out the sentence. One of the most effective portions of this story shows the aghori at home with his family but completely separate from them. He smokes ganja in the house and does prayer rituals on the roof in the middle of the night. Seeing the mortification on the faces of the family as they hide in their beds while the entire neighborhood comes out to gawk at the aghori was one of the highlights of the film. True divinity, says Bala in this scene, cannot coexist with societal propriety.

And Arya himself is phenomenal. If I hadn’t known him before this film I would never have been able to identify him in anything else. His eyes are glazed, his manner frenetic, and his voice a deep growl. He struts around nearly nude with wild hair flowing everywhere. And when Bala turns up the wind machine on some of those tight close-ups of Arya’s face, the effect is otherworldly. The aghori is divine and we are all nothing to him.

I was genuinely surprised when looking up reviews of Naan Kadavul to see that most critics were underwhelmed—saying that the script was weak, the film glorified violence, and/or dwelled too much on the cruelties inflicted on the beggars. I strongly disagree with all three critiques. The appeal of a film like Naan Kadavul is in the characters and their relationships to one another rather than in clever plotting and Bala gave even the smallest characters (literally, sometimes) room to breathe and become human. As for the glorified violence, it was no more graphic than in a typical masala film and I don’t think Bala was encouraging viewers to go out and begin beating people vigilante style. The film was a fable and the violence should be taken in that tone but I understand how somebody reading the film as “realistic” might be concerned with the violence because in Naan Kadavul, violence is handed out as punishment. Lastly, I don’t think the cruelties to the beggars were dwelt upon. Certainly all sorts of disabled actors were shown on screen and violence to them was hinted at but underlying it all was the feeling that these men and women were tough as nails survivors, not objects of pity.

Naan Kadavul is a film that sticks with you and one that I think would hold up well to repeat viewing. I kind of want to watch it again right now... and deliver a firm headbutt to anybody trying to stop me. Thank you, Bala, for a wonderful film!

(Originally posted August 12, 2011)